Mac Macauley and the Road to Fatherhood

With Father’s Day (June 21st) on the horizon, Mac Macauley, the gruff dad of our first publication “The Shiralee”, has been on my mind.

Macauley is definitely not a model father – in fact he’s far from it. He’s a tough itinerant worker traipsing across New South Wales in search of manual labour. His lifestyle is unpredictable, he frequently gets into violent brawls, he’s racist, a womaniser, and he makes no allowances for his four-year-old daughter Buster, who is travelling alongside him. He thinks of this little girl as a burden, which is what “shiralee” means; it’s an obscure nineteenth-century phrase for a swag and we are told on the second page of the novel that Macauley has two swags, one that he puts on his back and that holds his things, and the other “with legs and a cabbage-tree hat”, which is his real trouble. Buster prevents her dad from taking the jobs that he wants, from walking as long as he can and from claiming the freedom and independence that his life has always been rich in.

Macauley is definitely not a model father – in fact he’s far from it. He’s a tough itinerant worker traipsing across New South Wales in search of manual labour. His lifestyle is unpredictable, he frequently gets into violent brawls, he’s racist, a womaniser, and he makes no allowances for his four-year-old daughter Buster, who is travelling alongside him. He thinks of this little girl as a burden, which is what “shiralee” means; it’s an obscure nineteenth-century phrase for a swag and we are told on the second page of the novel that Macauley has two swags, one that he puts on his back and that holds his things, and the other “with legs and a cabbage-tree hat”, which is his real trouble. Buster prevents her dad from taking the jobs that he wants, from walking as long as he can and from claiming the freedom and independence that his life has always been rich in.

But as the narrative of this Australian classic winds it way through one dusty town after another, as Macauley and Buster bump into old friends, make new acquaintances and pick up the odd job or two on their way, we see a gradual but perceptible shift in Macauley’s attitude towards his daughter. He notices how tough she can be – “They had walked for two hours, and Macauley couldn’t help but observe, as he had been observing, the growing endurance of the little girl” – and how her adoration of him never falters regardless of his own behaviour – “She launched herself at the fortress of his strength and protection, refusing to be spurned”. Slowly, he comes to realise that this Buster is somebody he respects and he cannot help but be proud of her and love her. And whilst Macauley’s tough exterior never dramatically buckles we see his emotional barriers put under some serious strain, especially in the incredibly tense and dramatic final scenes of the novel.

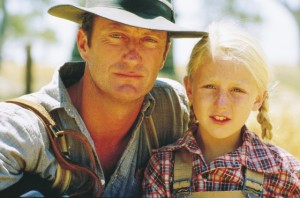

Bryan Brown and Rebecca Smart as Macauley and Buster in the 1987 TV mini-series adaptation of “The Shiralee”

It’s this morphing father-daughter relationship at the centre of “The Shiralee” that makes it such a wonderfully moving, powerful and relevant novel, even 60 years after its initial publication. It’s a timeless story of a dad getting to know his child and with such a universal principle it’s sure to touch any reader. But naturally it’s a novel that will appeal particularly to fathers. In his introduction to our edition, my colleague Nic writes about how reading the novel for the first time as a new father was especially gripping for him. Thankfully for his children, Nic is much a much kinder and more settled father than Macauley, but I know that Mac will always remain one of Nic’s all-time favourite literary dads, precisely because he is so flawed as a man and as a father – there’s something incredibly inspiring and fulfilling about his subtle transformation. I think Tim Winton summed up Macauley’s predicament perfectly in the quote that he sent us for the cover of our edition, he said:

“Sometimes our gravest burdens, the weights we drag with us along life’s potholed road, are the key to our liberation. For a generation of readers accustomed to the niceties of political correctness, The Shiralee may seem as brutal as it is lyrical. But with its insight into the way a child can, by the provocation of her own vulnerability and by sheer force of love, bring a grown man to his senses, The Shiralee is a novel that still rings true after more than half a century.”

And long may it continue to do so… Happy Fathers Day everyone!

By Kate Morris-Double